USDA Hardiness Zones: Choosing Plants According to Climate

The USDA Hardiness Zone system classifies regions of the globe based on their average minimum winter temperatures, helping gardeners adapt their plantings. There are currently 13 zones, ranging from extreme cold (zone 1) to the mildest climates (zone 13). The table below summarizes the minimum temperature ranges associated with each zone (in Celsius and Fahrenheit):

| USDA Zone | Color | Average Minimum Temperature (°C) | Average Minimum Temperature (°F) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | < −51 °C | < −60 °F | |

| 2 | −51 °C to −45 °C | −60 °F to −49 °F | |

| 3 | −40 °C to −34 °C | −40 °F to −29 °F | |

| 4 | −34 °C to −28 °C | −30 °F to −18 °F | |

| 5 | −28 °C to −23 °C | −18 °F to −10 °F | |

| 6 | −23 °C to −17 °C | −10 °F to −1 °F | |

| 7 | −17 °C to −12 °C | −1 °F to +10 °F | |

| 8 | −12 °C to −7 °C | +10 °F to +18 °F | |

| 9 | −7 °C to −1 °C | +18 °F to +30 °F | |

| 10 | −1 °C to +4 °C | +30 °F to +40 °F | |

| 11 | +4 °C to +10 °C | +40 °F to +50 °F | |

| 12 | +10 °C to +15 °C | +50 °F to +60 °F | |

| 13 | ≥ +15 °C (and above) | ≥ +60 °F (and above) |

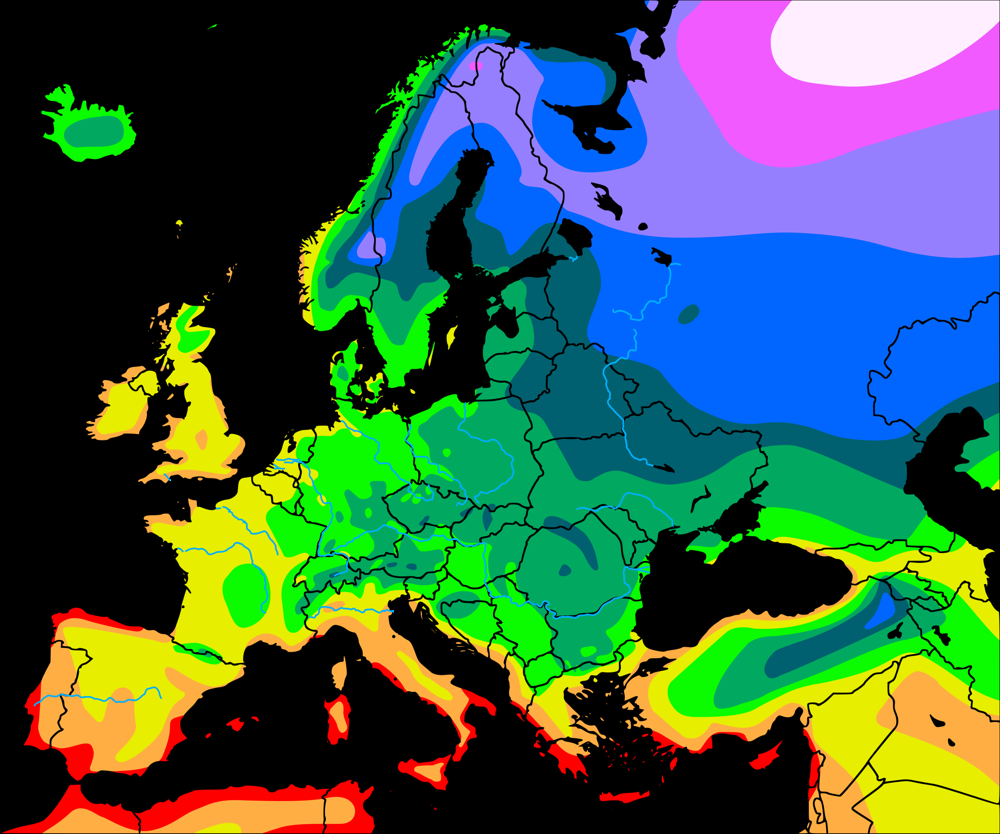

USDA Zones Map in Europe (source: Wikimedia Commons, CC0). It shows that hardiness zones vary greatly across Europe: Mediterranean regions are in zones 9-10 (minimum temperatures around -7°C to +4°C), while northern Europe and mountainous areas are in very low zones (1-5, temperatures down to -45°C). In France, for example, the Alps and Pyrenees are around zone 6 (about -20°C) and the Mediterranean coast is in zone 10 (down to -1°C).

What is the USDA System?

The USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) system is a climate scale based on average minimum winter temperatures. The USDA initially defined these zones from weather records in the United States, but the method has been adopted internationally because it is simple and precise. Specifically, each zone corresponds to a range of winter cold intensity. For example, being "hardy to zone 8b" means a plant can tolerate minimum temperatures around -9.5°C.

According to the official USDA website, this map is "the standard by which gardeners and growers can determine which perennial plants are most likely to thrive at a location." In practice, we compare the USDA zone of a location (or the garden's "hardiness zone") with the minimum zone recommended for each plant. Thus, to survive long-term, a plant must be rated for a zone at least as low (colder) as that of the garden.

What is it used for and why is it used worldwide?

USDA zones provide a single, globally recognized reference. Even outside the United States, many gardeners and plant catalogs continue to use these zones to simplify species selection. For example, if a shrub is labeled "hardy to zone 7," a gardener in zone 6 will know there's a risk of winter loss. Conversely, planting a zone 9 plant in zone 8 ensures it will survive the local winter. This method works for both northern and southern hemispheres as long as the local minimum temperature is known.

Outside the USA, there is no single global climatological classification, so USDA serves as an easy reference. Perennial and fruit tree fact sheets often indicate the USDA hardiness zone. In practice, we ensure that the "plant's zone" covers the "garden's zone." This helps predict whether a fruit tree (apple trees, citrus, etc.) will survive winter or if an evergreen perennial will withstand frost.

System Limitations

The main advantage of USDA zoning is its simplicity, but this is also its limitation: only winter cold is taken into account. This system completely ignores summer heat, humidity, winds, sunlight, or microclimate variations. For example, two regions with equivalent winter minimums (same USDA zone) can be very different: an oceanic humid climate or a dry continental climate can change a plant's ability to survive, even causing its death despite identical labeling.

Another limitation: current maps are averages over several years, they don't predict exceptional frosts or recent climate changes. Finally, the USDA zone is an average data: the local microclimate (sheltered location, south-facing exposure, water presence, protective snow...) can modify the actual hardiness of a location.

Tips for Proper Use

- Give yourself a safety margin. If your garden is in zone 8a, consider plants rated for zone 7b or 7a to compensate for potentially harsher winters. It's better to underestimate the required hardiness than the opposite.

- Consider the microclimate. For example, two locations in a city can differ by one USDA subzone: a sheltered south-facing balcony will often be warmer than a north-facing roof. In the same country or even the same city, you can sometimes gain or lose 1 to 2 zones depending on exposure and protection.

- Take other factors into account. Plan to protect sensitive plants (mulching, winter cover) especially if they are at the lower limit of hardiness. In case of very hot summer, some "hardy" plants don't appreciate excessive heat (think of Mediterranean fruit trees that need cool winters to flower).

- Use local sources. Online USDA maps (e.g., by postal code) give a general idea, but local gardening bulletins, regional nurseries, and local enthusiasts can refine knowledge of microclimates and indicate plants "tested" for your region.

European Equivalents

In Europe, we often speak directly of "USDA hardiness zones" as they have been widely adopted. In France, for example, the country ranges from zone 6 (cold winters in mountains) to zone 10 (mild winters on the Mediterranean coast). However, some countries have their own complementary classification: in the United Kingdom, the Royal Horticultural Society defines seven categories (H1 to H7) based on cold and shelter, with H7 corresponding to about < -20 °C (approximately equivalent to USDA zone 6a). Other Mediterranean or subtropical countries sometimes use maps directly comparing their climate to USDA zones.

In practice, we can remember that the USDA zone is often considered a de facto standard. For example, a rose "hardy to zone 8b" will survive in gardens rated zone 8b or warmer, regardless of the country.

Brief History of the USDA System

USDA zoning was created in the 1960s at the U.S. National Arboretum in Washington (first map in 1960, revised in 1965). Early versions used 10 °F (≈ 5.6 °C) intervals per zone. In 1990, the map was updated by introducing "a" and "b" subzones corresponding to a 5 °F (≈ 2.8 °C) difference. More recently, in 2012, the USDA redid the map based on 1976-2005 data, adding two new zones (12 and 13) to cover tropical and subtropical climates. This revision also refined the map's resolution (more precise zones). The Arbor Day Foundation and other organizations regularly publish updates (latest interactive version 2023 for the United States) reflecting global warming.

Role in Choosing Perennials and Fruit Trees

The USDA zone has become a key tool for selecting perennials, shrubs, and fruit trees. Plant labels and technical sheets often mention the minimum USDA hardiness. For example, star jasmine can tolerate around -15 °C, while many citrus trees (oranges, lemons) die at -7 °C. A fig tree (USDA zone 8) won't be introduced into a zone 6 garden as it would freeze. Thus, by comparing the plant's hardiness zone with the planting location's zone, we avoid growing unsuitable species. In summary, the USDA map helps predict whether a new plant will "survive winter" and guides the choice of species (flowering perennials, fruit trees, roses, etc.) adapted to each local climate.

Further Reading

-

Hardiness Zone (Wikipedia EN) - Article on USDA zones and their worldwide use

-

Zona de rusticidad (Wikipedia ES) - Article detailing the concept of hardiness zones

-

Hardiness Zones in Europe (Gardenia, EN) - English guide with Europe map and practical information

-

Blog EntreSemillas (ES) "Zonas de rusticidad: ¿Qué son y por qué son importantes?" - Educational explanations (in Spanish)